In the second of our series of interviews with scientists from the Wonders of the Living World book, we meet Dr Rhoda Hawkins. Rhoda is Senior Lecturer in Biological Physics Theory and Assistant Faculty Director for Postgraduate Research at the University of Sheffield, and is a committee member of Christians in Science. Here she shares her sense of wonder in exploring the world using the tools of science.

What got you into science?

As a child I loved being outside surrounded by nature. I was curious about the natural world, asked many questions and wanted to find out more about how things worked. I was interested in biology, but it was physics I was drawn most to because it seemed to underpin everything in science in terms of explanation. For me it was exciting to learn and understand more about God’s creation.

Can you tell us a bit about your faith journey?

I was brought up in a Christian family. My father was a vicar. I grew up mostly in the UK, after spending the first 3 years of my life in Africa where my parents were missionaries. Vicarage life had its challenges but also advantages. I met and learnt from varied and interesting people. I made much use of the access I had to the vicar by asking my Dad many questions. Seeing behind the scenes of a church showed me some messy realities not often on public display. Such things sometimes led me to question or criticise church or Christians, but I came to put my faith in God. I have continued to question things throughout my life. Rather than seeing such questioning as negative ‘doubt’, I see it as a positive part of my faith journey.

What role does wonder play in your scientific work?

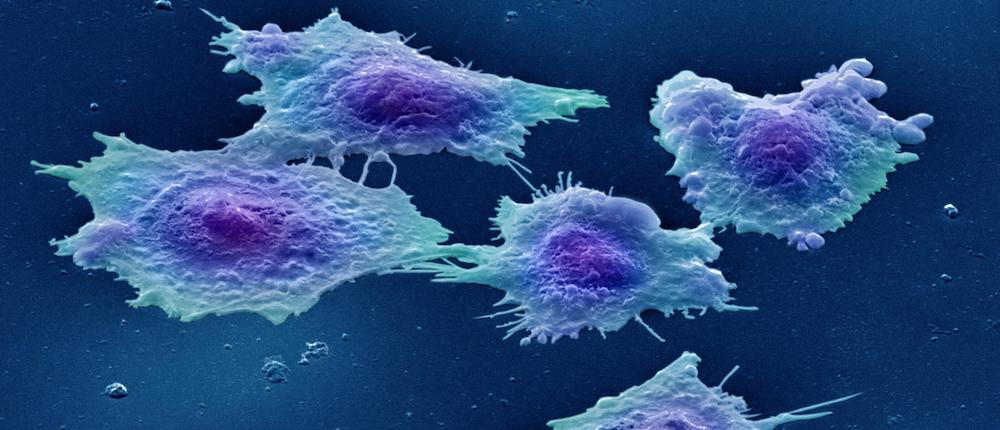

The main role wonder plays in my scientific work is inspiration and motivation. My wonder at the natural world is what drives me to find out more about it. There are two senses of ‘wonder’ that are important to me in my scientific work. One is wonder in the sense of awe and the other is in the sense of questioning. These two types of wonder feed off each other. Awe of something I see in my science leads me to question further. For example, I may see a beautiful microscopy image of a tiny structure and ask what causes it to have the shape it has. If my work leads to an answer to a question like that, I am then filled with wonder at the answer.

Data from a recent study[1] show that biologists tend to find complexity beautiful, while physicists are more likely to admire simplicity. Which aspects of the things you study do you find beautiful?

As a biological physicist I can see both sides of this. I often find microscopy images of complex systems beautiful in the sense of them being pretty. However, I admire the elegance of a simple explanation – sometimes in the form of a simple equation. This second kind of beauty, or elegance, is deeper and more satisfying to me. Complexity is more beautiful if I can explain it in simple terms. So whilst I can see a form of beauty in complexity, I admire the beauty of simplicity more. I am a physicist after all!

The same study found that 66% of scientists feel a sense of reverence or respect about the things they discover, and 58% feel as if they are in the presence of something grand, at least several times a year. Can you describe a time when your scientific research gave you a similar sense of awe?

Recently a PhD student of mine has been doing computer simulations to try to find out how a particular striped pattern of proteins forms in certain cell types. We knew from experimental microscopy data what the pattern looks like and what it is made of. We developed a simulation including the ingredients we thought were important. We kept running the simulation with different amounts and properties of the ingredients but we saw no pattern. After nearly two years of trying different possibilities one simulation suddenly showed a striped pattern. ‘Wow’, was all I could say when I saw that result. I had a sense of reverence, partly since the answer was unexpected and my initial ideas had all been wrong. It felt like discovering or seeing something bigger than my own ideas.

When Wonders of the Living World was written you mentioned some big questions about meaning and purpose that your work raises. Are you still asking similar questions today, or has your thinking moved on in any way?

I am still interested in the questions such as ‘How is living matter different from non-living matter?’ and ‘How can order emerge from disorder?’ However, much of my day-to-day work is on a less grand scale. We often work on smaller projects that are relevant to these big questions but are sub-questions in their own right. For example, my PhD student’s project on how a particular striped pattern of proteins forms is an example of order emerging from disorder.

One thing I am excited about at the moment is our work on how immune cells engulf pathogens. We have recently made some interesting progress on this and are planning further work to test our ideas.

During the pandemic much of my focus has been on supporting PhD students whose work has been disrupted by lockdown. I have also missed being able to talk with other scientists in person at conferences. It is hard to have creative discussions online. This recent experience has shown me even more how important creativity and personal interactions are in science.

What sorts of questions do you think you will be asking, or would like to be asking, in your work in ten (or twenty) years time? Might your future discoveries raise even more big questions of meaning or purpose?

Over the next ten years I would like to focus more on the interaction between blood cells and infectious microbes. This is a question of great importance for many diseases and might even one day lead to improvements in treatments.

In ten or even twenty years time I expect I will still be asking ‘How is living matter different from non-living matter?’ but I hope to have made progress on this by then. If so, I will then be able to ask further questions about how life is sustained.

[1] https://workandwellbeingstudy.com. 3442 scientists in physics and biology departments in India, Italy, UK, and US completed the survey.