Are we alone in the Universe? This question has teased scientists and philosophers for many decades and is a central theme in much science fiction writing. More recently, as planets have been discovered in solar systems other than our own, the question has returned. Could there be another Earth-like planet colonised by living organisms out there somewhere? This field has become so important scientifically that it is now regarded as a separate discipline – that of astrobiology.

A possible answer to our uniqueness (or lack of) came in the mid 1990’s when it was claimed that there was evidence for life on Mars, our near planetary neighbour. In many ways Mars is a very likely candidate for life. Mars is Earth-like in its form, although only half the size of the Earth, and may represent a planet that did not properly ‘grow up into adulthood’. However, we now know that – unlike other rocky planets – Mars once had water on its surface. Images of the Martian surface show the scars of former river channels and lakes together with rocks of sedimentary origin which must have formed in these ancient watery environments. Water is vital for the development of life so these ancient sediments, perhaps 3.5 billion years old, could have hosted primitive life forms.

Results from a Martian meteorite

The first major claim for former life on Mars was made in 1996 by a group from NASA and published in the scientific journal Science[1]. Their work was based on the study of a fragment of Mars preserved as a Martian meteorite, recovered from the ice-fields of Antarctica and catalogued as sample ALH84001. Detailed examination of ALH84001 under an electron microscope revealed some extraordinary ‘fossil’ structures made of calcium carbonate resembling shapes created by nanobacteria today. In places these shapes were organised into colonies and looked very much like former living organisms. In addition there were carbon-rich molecules present known as PAH’s (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) which were also thought to be biological in origin. Also significant were tiny crystals of the iron mineral magnetite present in the mineralised carbonate vein, mineral grains which had an identical crystalline form to that of magnetite formed today in a biological setting.

These findings were heralded with a great fanfare of publicity – NASA press conferences and even a speech by the then American President – Bill Clinton, but sadly subsequent less high profile science progressively dismantled the ALH84001 Martian life hypothesis. Curious nano-scale structures alone are not sufficient evidence of former biology, the magnetite grains were also found to be abiogenic and the PAH’s thought to be terrestrial contamination. Nevertheless, almost directly as a result of these findings, a new NASA Mars programme was initiated the results from which are now becoming very exciting.

New findings from Mars

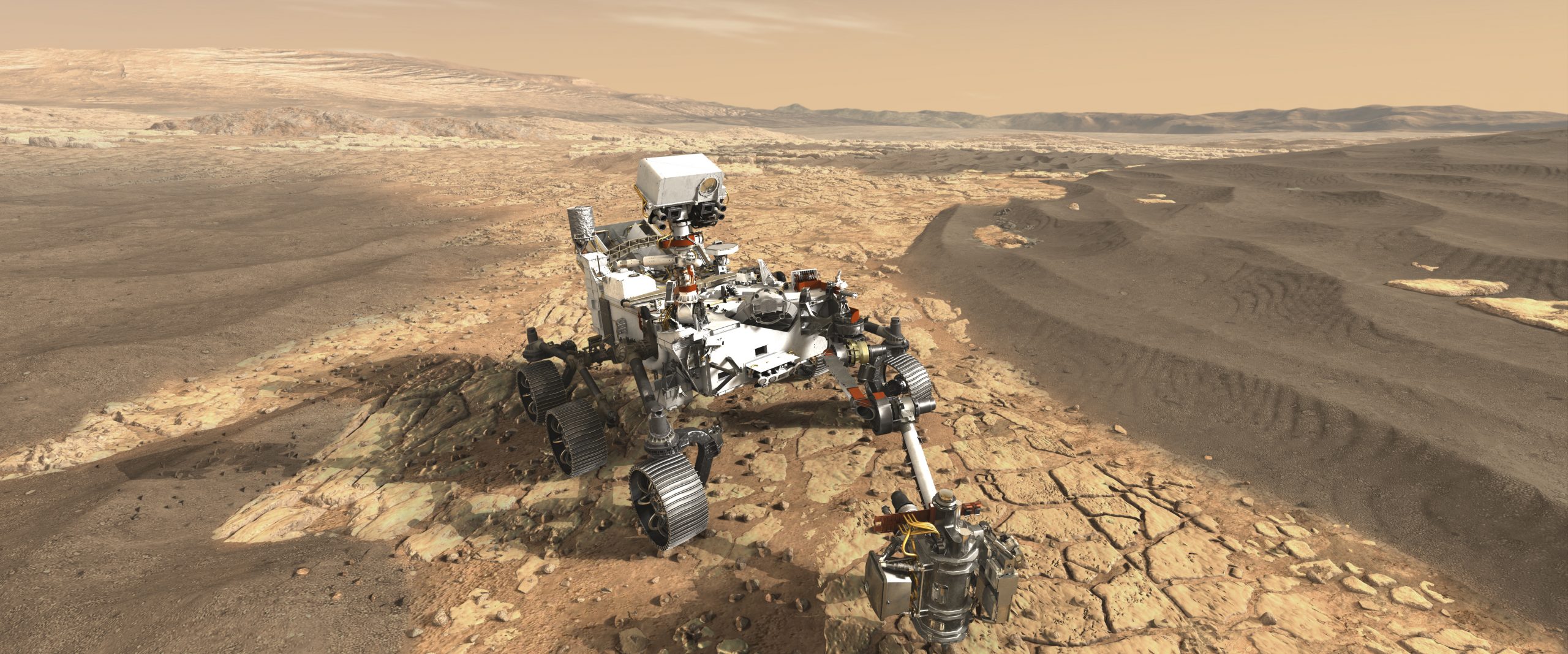

Earlier this year, in June 2018, a different team from NASA cautiously announced new evidence for possible former life on Mars in the journal Science[2]. The new results are the latest work of the Martian rover Curiosity and its miniaturised on-board analytical laboratory. Curiosity has the capacity to drill into the Martian subsurface and chemically analyse the rock materials it samples, sending the results back to Earth. Part of the analysis is to detect the presence of carbon based molecules – organic molecules as they are known – which could be of biological origin. Most recently Curiosity has been located in the Gale Crater on Mars and has been drilling into mudstones dated at 3.5 billion years old – rocks formed at a time when we know life was already present on Earth. The Gale crater is the site of a former lake fed by an ancient river system – a very plausible location for life to develop 3.5 billion years ago. The new results show the presence of a number of carbon-based molecules of varying complexity, although none as complex as those expected from former living organisms.

What might these new results mean?

So now the scientific question is what do these results mean? We know that carbon-based molecules do exist in space. For example, a particular type of meteorite family known as ‘carbonaceous chondrites’ can be rich in a tar-like substance made up of carbon-based materials and these must have been generated within the solar system. So it is possible that the Martian organic molecules are nothing to do with life and were simply delivered from space, deposited on the Martian surface and subsequently buried. Alternatively, they could be fragments of larger molecules, perhaps of biological origin, which have been degraded through burial and solar radiation. What we can be sure of this time is that these results are not the product of contamination. Scientists have waited several years before releasing these findings during which time they have satisfied themselves that their results are not an artefact of their method.

So we currently do not have solid evidence for life on Mars, but we now have a methodology that works and a potential source of data to explore. These results are just the beginning and we must await with interest further findings from the Martian Curiosity rover and its successor to be launched in 2020 as they explore further the Martian surface.

[1] McKay et al. Science 273, 924-930 (1996)

[2] Eigenbrode et al., Science 360, 1096–1101 (2018)

Professor Hugh Rollinson was Course Director at the Faraday Institute and is Emeritus Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Derby. After graduating from Oxford Hugh worked for a number of years as a field geologist in the Geological Survey of Sierra Leone. This was followed by a PhD at the University of Leicester and then a post-doc at the University of Leeds. He then joined the University of Gloucestershire and worked there for 20 years, during which time he took a three year leave of absence to work as Associate professor of geology and head of Department in the University of Zimbabwe. He then took a position as Professor of Earth Sciences and Department Head at Sultan Qaboos University in Oman for six years after which he served as Professor of Earth Sciences and Department Head at the University of Derby. Hugh’s academic interests are in the earliest part of Earth history – the first two billion years of planetary evolution and these are summarised in his text ‘Early Earth Systems’ (Wiley-Blackwell, 2007).

Hugh has had a life-long commitment to the Christian faith and has sought to integrate his beliefs with his scientific work. This has largely been through serving the local church wherever he has lived. He has a strong commitment to making the Christian faith accessible and engaging in dialogue with those who hold divergent views.