Conservation work falls at the interface between pure biological study and the philosophies, politics, needs, attitudes and general realm of human beings. This meeting point is something that has attracted me ever since I was introduced to fisheries science at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. I was drawn in by the multi-disciplinary nature of the field, which uses mathematics and models alongside pure biological knowledge to study and advise fishing practices. However, in order for any advice to be taken on board by decision makers it also has to (understandably) account for human employment needs, financial viability and market demand or human preference.

I vividly remember an exercise where our class was given a theoretical stock of wild fish to manage, using a simple spreadsheet. With the class split into groups of politicians, environmental lobbyists, scientists, fishermen and general public, appointed decision-makers had to sustainably manage the stock while accounting for the demands and pressures of each group. Balancing catch-limit advice from the scientists with the employment demands of the fishermen, species-specific demands from the public, new-age boats with more efficient fish-locating equipment, and the government’s vested interest in keeping the voting public happy in the run up to the next election was a challenge none of us had previously encountered or practically considered.

Before starting the exercise, our young and enthusiastic class was very excited to show that if we were in charge of matters, things could be done sustainably and successfully. I am sad to report, however, that our hypothetical fishery collapsed. Now this is not an article on the overexploitation of our planet’s resources, but rather it sets the scene for what I – after working in the conservation world – like to call working on the conservation frontline!

Before coming to work at The Faraday Institute, I spent a year managing conservation projects in The Republic of Maldives; and what a beautiful frontline it was!

The ocean is bluer than I could ever have imagined; the fish more colourful, the manta rays more graceful, the turtles more beautiful, the sand whiter and the reef more inspiring. Being able to enter into this underwater world with such ease on a daily basis was a true blessing. There were moments when I would dive underwater and find myself surrounded by a large school of fish; snorkelling next to a slow ‘chilled out’ turtle; or floating into an oncoming stream of feeding manta rays. At these times, an overwhelming feeling of contentedness, joy and appreciation would well up inside me at the beauty of the scene.

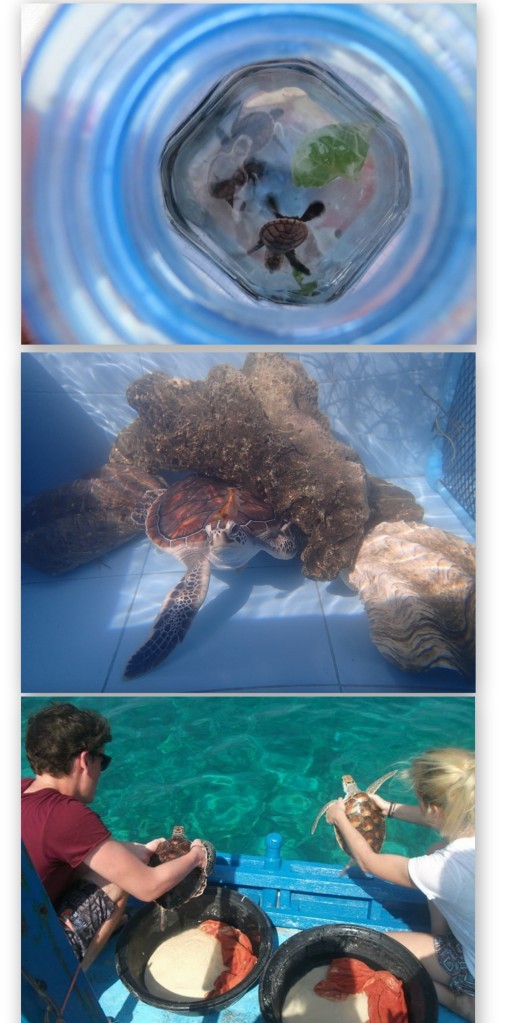

Back on dry land, we at Atoll Volunteers ran educational classes, environmental awareness events, and were in charge of the daily management of the marine centre and turtle sanctuary.

There are 5 species of turtles found in the Maldives. We encountered two species during our work: green turtles (Chelonia mydas) and hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata). The IUCN Redlist categorises green turtles as ‘endangered’ and hawksbill turtles as ‘critically endangered’ (this, incidentally, is one category below ‘extinct in the wild’). Although they are marine animals, these gentle giants are also air-breathing and land-nesting, so are directly tied to the human world and human activities. Turtles suffer boat injuries, litter entanglement, nest-poaching, loss of nesting-beaches, poaching for their meat and being kept illegally as pets in poor conditions.

In this setting, our turtle sanctuary provided an avenue for these endangered turtles to recover and grow before being released back into the wild. Policing of pet turtle owners is a constant problem so, using educational outreach, we appealed to the local adults and children to voluntarily donate their turtles to the centre. We then raised them in larger tanks, using correct sea turtle husbandry protocols until each turtle was large enough to be released. So before the stunning underwater scenes and tropical postcard-perfect photos make you think that it was all play and no work, I must slip in a brief mention of the early mornings, tank scrubbing, exhaustingly hot and humid weather, and the pre-breakfast routine of preparing the turtles’ breakfast. This preparation involved getting a concoction of fish blood and the contents of fish ovaries, testes and livers under ones nails, which was all fun and games – until I also mention the fact that we were expected to then eat our own breakfast with our hands!

Working with the turtles was an intensely satisfying job, and I feel privileged to have been so closely involved in the care of just a small portion of the natural world. Being directly responsible for the daily care of these creatures aroused a feeling I can only liken to motherhood, heightened by the feeling of loss as they ‘flew the nest’ upon release into the ocean. Added to their aesthetic beauty is the fact that each individual turtle had unique physical traits, attitudes and even personality.

For example, deciding which turtles would be placed into tanks together took a great deal of experimentation and sensitivity to ‘turtle politics’ or conflicting personalities. We could not house a bully with the more timid individuals, but found that two bullies – after sizing each other up – could co-exist. We had to learn and adhere to different turtles’ food preferences. Some liked resting on the surface, and others under rock alcoves. Some loved being cleaned gently with a toothbrush, but others not at all. Some were even recognisable by habits such as creating and chasing bubbles or using sharp bursts of speed that saw them spinning into others and then hastening away.

Did you know that each turtle in the world has a unique fingerprint? The scales on the sides of their head form a unique pattern that, if recorded, can be used to identify the individual even when they have grown up.

Similarly, you can identify manta rays to the individual level based on their ventral markings.

Where possible, (it is harder than it sounds) we photographed the undersides of manta rays and profiles of turtle heads in the wild. The relevant monitoring programmes (Sea Turtle Monitoring Project and the Manta Trust) used these submitted images to track individual turtle and manta ray movements throughout the Maldives.

This amazing and beautiful level of individual detail fills me with even more awe at creation. God did not make a rigid, identically replicated template for every animal. The mechanisms he put in place produced a system which is so much more than that. To be able to work in a world with not only many different species, but also a huge diversity of traits and characters within species, adds to the wonder of creation; a creation where even every turtle in the world is a unique individual.

In Matthew 22:37, Jesus says we should love God with all our minds. I am newly excited to continue my scientific career intentionally living out that synergy and devoting ‘mind-time’ to thinking about how I can praise God and serve creation at every frontline I encounter.