I have been exploring the question of purpose in biology. Science can only go a very little way toward answering the question, what is the point of being alive? Meerkat adults feed their young so they can grow big and strong, and antelopes bound away from leopards so they can feed in peace. I think it is quite legitimate for a scientist to ask questions about this very limited kind of biological purpose in the course of their work. Some might disagree with the terminology and prefer to talk about ‘goal-oriented behaviour’, or want to remind us that these choices are made unconsciously. Either way, many scientists would agree that something is happening in order to achieve an end – but that’s as far as it goes.

Most people are more interested in questions of ultimate purpose: ‘What is the meaning of life?’ These questions are often raised by science, but science itself cannot answer them. For example, Professor Simon Conway Morris of Cambridge University has studied the way in which the same structures such as wings, legs, or eyes like ours appear time and time again in completely unrelated species. It’s as if there is only one really efficient way for the processes of biology to complete the journey – the biological purpose – of finding ways to get around or see. For him, these data suggest that there is a deep structure behind the universe: a set of physical constraints or pathways that we are only just beginning to understand. But his work also raises a bigger question.

The theologian and former scientist Alister McGrath likes to look at the world through the lens of Christian theology. He asks, does belief in God bring the things we uncover using the tools of science into sharper focus? For him, science does not provide proof for God, but its findings are compatible with belief in a loving purposeful God. Similarly for Simon, although he never even speaks of evidence for God, the idea that life is going in a particular series of directions seems consistent with the human instinct that there is an ultimate purpose to life, and with his own belief in a Creator.

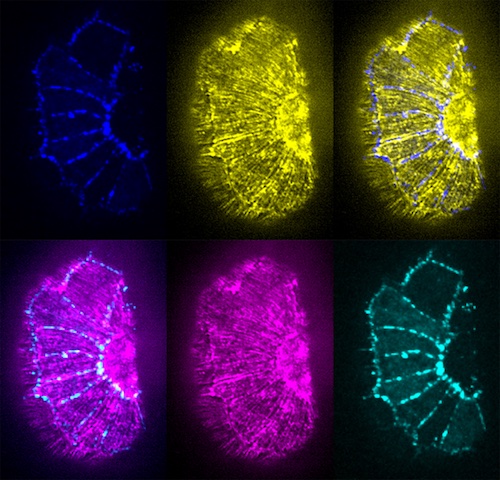

In the course of writing Wonders of the Living World I was able to meet several scientists, asking them about the questions of meaning and purpose that their work raises and how their faith points them toward potential answers. Jeff Hardin is Professor of Integrative Biology at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where he studies the ways in which cells attach to each other as an embryo develops. Jeff studies worm embryos, because they share many of the same basic properties as humans. He and his research team capture microscope images that could rival the stained glass in a cathedral. His work moves him to explore the meaning of this beauty, and ultimately to worship God. Jeff also finds that his scientific knowledge heightens his sense of wonder at the fact that Jesus was once an embryo

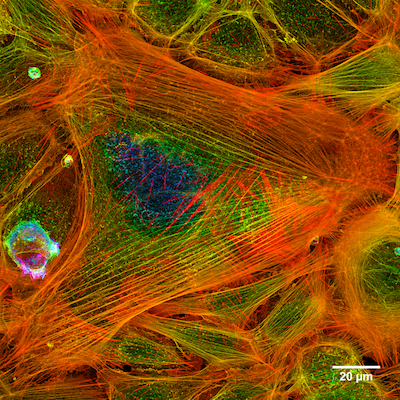

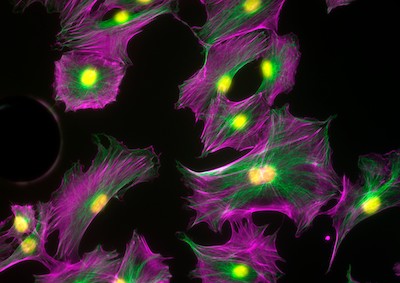

Rhoda Hawkins is a Senior Lecturer in theoretical physics at the University of Sheffield. She studies the ways in which random movements on a small scale can cause patterns to emerge at larger scales. For example, the water molecules inside each cell in your body are moving around at random, bumping into everything. This movement gets other molecules in contact with each other in ways that are useful to the cell. For instance, the cell has a type of skeleton which helps it to take shape and move in different directions. This structure is made of long lines of specialised molecules that stick to each other in a certain direction like Lego blocks. The blocks – pushed around by the water molecules – are more likely to fall off one end of the line than the other, so it grows at one end and shrinks at the rear. With some additional energy input, the combined movement of many lines of blocks can push the cell’s outer envelope in one direction, causing the cell to move along.

One of the most fascinating sights I have seen on a winter evening are the huge flocks of starlings that wheel around as they come in to roost. Many thousands of birds can fly together in a single, huge group known as a murmuration, and each time the flock changes direction it pulsates and changes shape in weirdly synchronized ways.

These flocking behaviours arise spontaneously when large numbers of animals come together. Each bird is self-propelled, but a collective behaviour emerges. Flying close together helps the birds to avoid predators as they come in to their roosting site. As they fly, they steer in an average direction. Whenever they change direction, they have to avoid crashing into each other – so they may need to change the formation they’re flying in. When these three rules are programmed into a computer, the same wonderfully organic-looking process is produced. On a much smaller scale, a similar process is happening to a group of molecules inside a cell when it moves.

If an entire flock of birds were captured in a very fine, light net, they might keep on moving by pushing on the inside of the net to change its shape and position. In a similar way, a cell moves when its internal skeleton pushes against its outer membrane. Like starlings coming in to land, the molecules inside that cell are constantly moving, but there is an overall pattern to the movement. Random motion brings the subunits together, but energy helps the filaments to form in a certain way and keeps them moving along. The subunits of each filament are constantly moving as more and more subunits are dropping off one end and being added to the other, pushing against the outer membrane of the cell.

So does the emergence of order from disorder suggest anything about how life began? This is a very active area of research, with a good number of clues but not many answers right now. Christians differ in their interpretation of the data, but it’s worth checking out the latest science before diving into the theological debate.

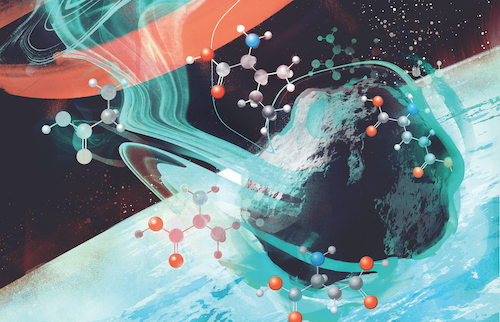

Astronomers have discovered that the intense heat of the stars turns hydrogen and helium into all the other atoms in the periodic table. When a certain kind of larger star runs out of energy it explodes, releasing a giant cloud of dust and gas known as a nebula that can produce new stars, meteorites, and also planets. When life first developed on Earth the conditions were probably very wet, with an atmosphere of simple molecules (including carbon dioxide), and a constant bombardment of radiation. Some scientists think that the molecules of life were formed in this environment. There is good evidence of organic molecules forming on meteorites, and they may have been the route for these compounds to reach Earth. (NB. This is very different to the idea of microbial life travelling to earth from elsewhere in the universe, which is not a popular theory at the moment.)

The incubator for life was probably a warm spring either in the deep ocean or at the Earth’s surface. DNA – the enormously long information-containing molecule contained by every living organism today – was probably a late arrival on the scene. Simpler molecules made of RNA (which is similar to DNA but more versatile) were probably the key players early on, interacting and reacting to form replicating units. Others think that the key factor was a series of interactions called metabolism involving proteins or possibly RNA. These molecules may have been enclosed in a membrane, especially later on. Throughout the whole process of the development of life on earth, the types of random processes that Rhoda studies would have been incredibly important in producing the order and patterns that are so important in the complex inner world of the cell.

Is it possible that the processes I’ve described here produced life? What does that mean for faith? Some Christians believe that the biblical account of origins is not just theological, but also scientific. They see a fundamental clash between the Genesis 1-3 account of origins and the scientific account, and sometimes seek alternative explanations. Others take a different approach, looking for evidence of design in the mechanisms and structures of living things. Many others, including the scientists and theologians described here, believe that the Bible and science tell complementary stories.

Rhoda, Jeff and the other Christians in the sciences who I work with believe that everything belongs to God. We don’t need to separate material things from the spiritual, as if God is absent from the material realm and that scientific explanations for life are in opposition to belief in creation. Rhoda believes that God could use random processes like the ones she studies in order to create, intentionally and purposefully. Like Simon Conway Morris, she finds that the data don’t tell her to believe in God, but they are compatible with his existence.

This post was reproduced from the Premier Radio Unbelievable Show Blog, with permission.